History

William Everitt: An engineering luminary

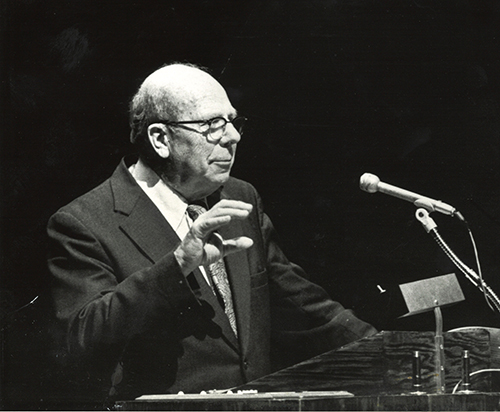

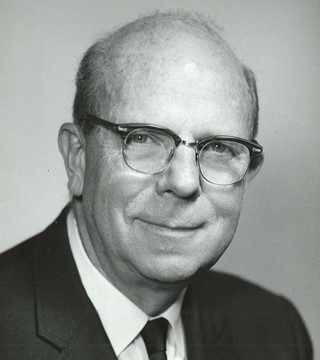

An inventor, author, exemplary educator, and engineering visionary, William Everitt helped transform the Illinois Electrical Engineering (EE) Department and College of Engineering into the research and education powerhouses they are today through his leadership in the two decades following World War II.

Everitt rose to prominence during the late 1920s and 30s when he wrote the book Communication Engineering while at Ohio State University. The book was one of the first anywhere to incorporate research results—largely his own—in a form suitable for classroom instruction. Reprinted in three editions, the book also introduced several generations of students to the nascent telecommunications field.

During World War II, Everitt led the operations research staff in the Army Signal Corps, making important contributions to radar development and training, including his inventing the radar altimeter which in some form is used in all aircraft to this day. From this experience, he recognized that the technological breakthroughs that were helping win the war were fueled by the work of scientists and physicists rather than engineers.

Being an astute and visionary educator, Everitt saw an opportunity to remake engineering education after the war. In 1944, he published this vision, "Phoenix: A Challenge to Engineering Education," where he explained his concept of a designed curriculum.

"Engineering education is now being burned by the fires of a technological war," he wrote. "Will it arise from the ashes like the Phoenix of old, with a rejuvenation...and the vigor to attack and solve its problems? Or will it simply continue on the path laid out by the old curricula and methods after a temporary recess? The choice is plain, and must be made by engineers and educators now, if a Phoenix is to be ready when the war is over."

When he became EE department head at Illinois in 1945, he led the curriculum transformation and hired some of the brightest young faculty, who would not only teach but would conduct research, as well—a novel idea at the time. In 1949, he became dean of the College of Engineering and implemented these reforms college-wide for the next 19 years.

Everitt also held nearly every major office in key professional and engineering education societies from which he was able to influence curricula change on a national scale. He worked in concert with other prominent engineers like Fred Terman at Stanford and Vannevar Bush, who founded Raytheon and pushed for the creation of the National Science Foundation.

"My grandfather was an accomplished engineer, and on that alone he could be remembered," said his grandson William Everitt III. "He was also an accomplished educator and on that alone he could be remembered. But what his legacy really is, and where he did change the world, was creating the philosophical foundation for which a first-tier research university can build itself."

During his tenure, Everitt hired key faculty who were or who would become internationally recognized as leaders in their field—people like two-time Nobel laureate John Bardeen, light-emitting diode (LED) inventor Nick Holonyak Jr., and silicon technology pioneer Chih-Tang Sah, for example. They, in turn, attracted additional luminaries who educated thousands of Illinois engineering students while also advancing research and technology.

According to Everitt's daughter Pam, he knew how to attract brilliant people and gave them the means to succeed. "I asked him once what he did to make Illinois so great and he said: 'I hired the best in each field, expecting they'd know more than me in their area. I tried to support them, and I let them go do great things,'" she said. "He valued other people and was never threatened by them being better than he was in their field."

A humble, compassionate man with a great sense of humor, Everitt loved the outdoors and enjoyed sailing, camping, hiking, and swimming. He volunteered his time with many civic organizations, including a stint as president of the Champaign Rotary Club. He regularly played Santa at his daughter's school and donned the costume as a volunteer bell ringer during the Christmas season.

Everitt and his wife Dorothy raised three children of their own—Barbara, Bruce, and Pam—and they welcomed dozens of international students into their Urbana home over the years. Two of those students were Chih-Han and Chih-Tang Sah, who fled the communist revolution in China in the late 1940s after their father, a friend of Everitt's, died. The brothers finished high school in Urbana and Chih-Tang earned bachelor degrees in EE and physics at Illinois. Later, he made pioneering contributions to silicon device technology while in industry and then joined the Illinois EE faculty, where he remained for more than 25 years.

"They escaped China and into the arms of my grandfather, who never looked back and treated them as much as family as anyone," said Everitt III.

According to Pam Everitt, her father's compassion was best exemplified when he invited a young Japanese engineering student to stay with his family when local landlords refused to rent to him. Only four years after the war ended, many people still harbored resentment toward Japan.

"In 1949, no one had Japanese and Chinese people living in the same house at the same time,' said Pam, noting how her parents provided an accepting environment for all their guests and set a great example for others.

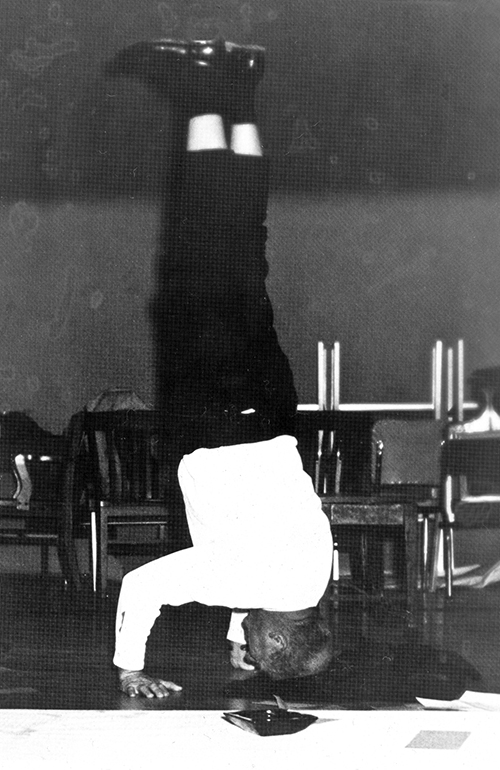

Everitt was perhaps the only engineering dean in the world who entertained students and colleagues with a headstand. According to a 1970 Chicago Tribune article, Everitt initially learned this feat in his twenties because he'd heard it might help ward off baldness. Although that didn't work, Everitt continued doing it well into his 60s, telling the newspaper: "...While my bald head attests the fact that this is no way to grow hair, I'm hoping the trick may keep me lively and contribute to my longevity."

Everitt retired as dean in 1968, but he continued to influence U.S. telecommunications policy and direction through National Academy of Engineering and Department of Commerce committees and panels.

During his lifetime, Everitt received many prestigious awards and honors, including the Institute of Radio Engineers Medal of Honor, he was named one of the two top electrical engineering educators by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, he was a founding member of the National Academy of Engineering, and he received 10 honorary doctorates.

He died on September 6, 1986, at the age of 86.